Explanation

The Ten Commandments: God’s Law of Love

We may think “moral law” is hard to prove, but it turns out the laws of the physical world can be just as elusive. Where should we turn to find the truth?

Explanation

Connection

Podcast

Edmund: Growing in the courtyard garden at the University in York, England, is an important tree. It’s an ancient apple tree. This tree started life as a graft cutting, which was taken from Sir Isaac Newton’s garden at his home in Lincolnshire. In the late summer of 1666, that very tree from which the cutting was taken, helped Isaac Newton question the nature of gravity.

Here’s the problem: you may have heard, or even said yourself, that Isaac Newton “discovered” gravity. But it seems silly to believe that a man in the 1600’s discovered something humans have experienced since the dawn of time.

Isaac Newton didn’t invent or discover gravity in the sense that he found something no one had ever found, or invented something no one had ever thought of. Instead, he began to think in a new way about something that has existed for all time.

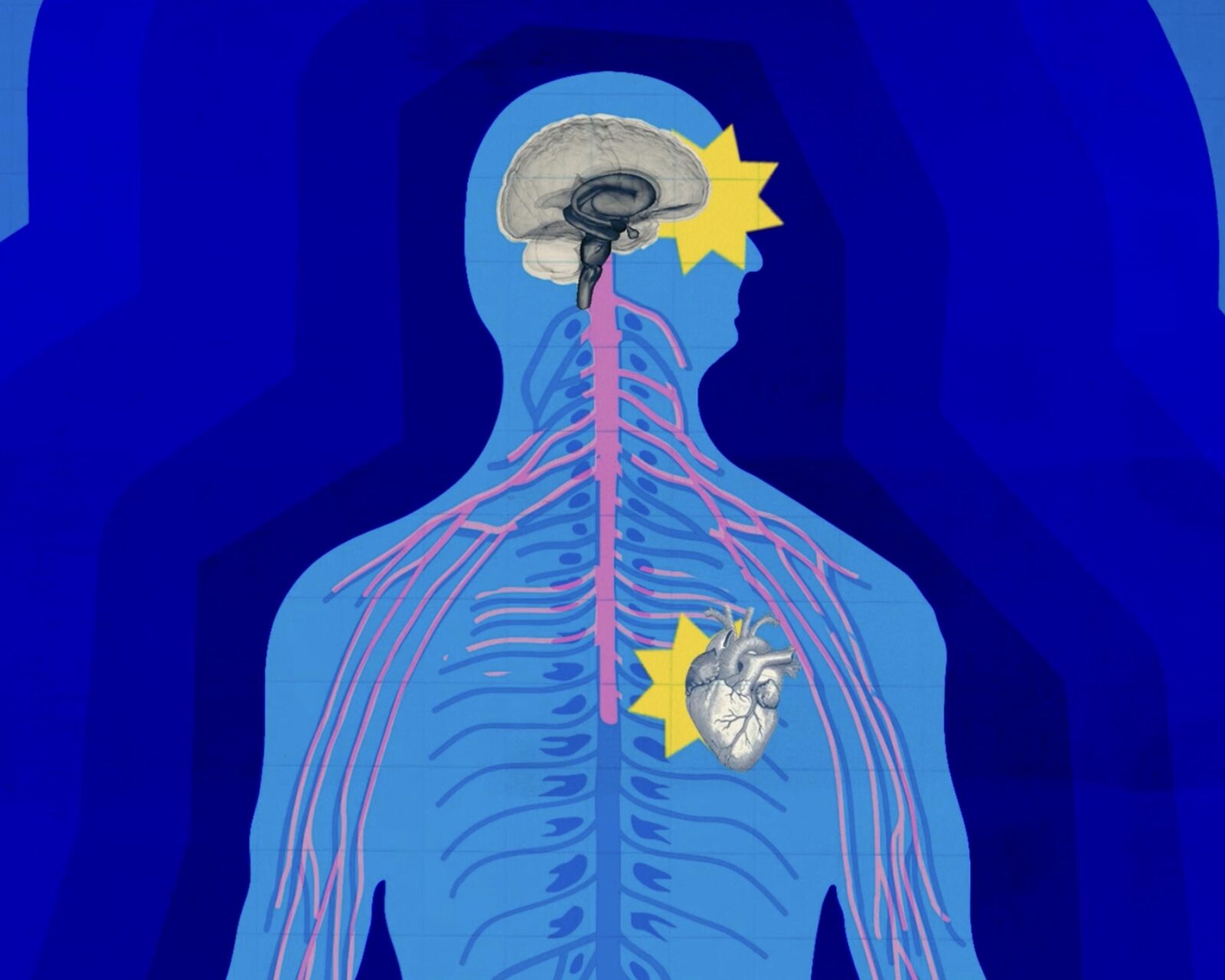

Scientists explore the natural world and define the things they observe. One important part of scientific inquiry is the ability to accurately predict how the world will behave. This leads scientists to define “laws of nature”. You may remember these laws of nature from school. For example, Newton’s law of gravitation, his laws of motion, or Boyle’s law about gas under pressure.

When scientists, like Sir Isaac Newton, observe that things fall to the ground, they attempt to describe reality in a way that is universal, accurate, and can help them predict other phenomena in the world. Newton’s law of universal gravitation states: “Every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.” Wow. Okay, that’s a lot from one apple.

But what do we do when we find that a seemingly settled law of nature is suddenly contradicted? For example, light has no mass and therefore should not be affected by gravity. Yet, it is affected by gravity through a process called gravitational lensing. Years after Newton, another scientist, Albert Einstein, advanced a more nuanced understanding of how gravitational forces work on objects in his theory of general relativity.

One way to reconcile Newton and Einstein is to imagine laws of nature as definitions that always sit within an assumed framework for understanding the world. When scientists find out that a law isn’t always true, they can either revise the law or revise the framework for understanding reality. For example, in Newtonian physics atoms and their parts are thought of in the same way we think of planets revolving around the sun. The famous Double Slit experiment and other experiments showed scientists that it wasn’t just the law that was inaccurate; instead, viewing atoms and particles as discrete objects didn’t tell the whole story. This was the birth of quantum physics, which describes more accurately the way things behave and interact at the atomic and subatomic scale.

Things get more and more complicated when we move from the physical world and start talking about human persons. For example, the field of psychology is filled with hypotheses that rely on many different frameworks for understanding the human person and the mind.

In “Mere Christianity,” C.S. Lewis asks us to imagine being on a bus or train and overhearing two people quarreling about a seat. We might hear the two people say things such as “That’s my seat, I got here first” or “Why should you get first pick of the seats?” What we can learn, he proposes, from listening to these arguments is that there seems to be some kind of law or rule of fair and decent human behavior that these two people are appealing to. Fighting, he says, is a physical action, but quarreling is attempting to show that the other person is wrong.

In other words, even if two people have different ideas about what is just or fair, they share a common understanding of the principle of fairness itself and therefore how people should act in this situation. We’ve now entered the realm of – morality!

When we say certain human actions are “right” or “wrong”, we’re defining a moral law people ought to follow. This then brings up an old question people have debated for centuries: How do we determine if we’re right about these moral laws? What we’re really debating is whether there is such a thing as an objective, universal, moral, law. And by this we would mean a law that would be true for everyone. And this moral law would contain truth about more than just a human action. It would also speak to something universally true about the human person and about the nature of reality itself.

All moral laws assume a “destination” or “end” for the human person. Just as the law of gravity implies a framework for understanding nature in which matter is made up of particles, moral laws imply a pre-existing framework for understanding what a human person is made for. If we hear someone say “You should not lie” without knowing the end we’re trying to reach as human persons, it’s hard to know if this particular moral law is true.

So what is the framework, nature, destination, or end we should use to understand the human person? What are we made for? And where are we going? And what turns should we avoid if we want to get there?

U.30 — CCC 1716-1729

If happiness is a fundamental desire we all have, and something we naturally seek out, why is it so hard to find?

WatchU.28 — CCC 1949-2051

Not many of us want to be the villain, but we’ve all done things we’re not proud of.

WatchU.27 — CCC 1803-1948

By putting others first, you can transform your heart and your neighborhood.

WatchU.26 — CCC 1730-1802

As humans, we think, feel, and decide to act. So the question we’re left with is: how will you use your free will to act?

WatchBy submitting this form you consent to receive emails about Real+True and other projects of OSV.